Shigeki Matsubara1,2,3

DOI: 10.5935/0004-2749.2025-0090

Dear Editor,

Two recent articles on generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) in academic writing warrant attention. Liu et al.'s review(1) stands out, and Ambrósio et al.'s(2) insights are particularly astute. While both papers highlight GenAI's impressive capabilities, they also express concerns about its drawbacks, particularly the risk of over-reliance on it. To complement their concern, I outline a hypothetical, undesirable future scenario that GenAI might bring to academic publishing. Rather than offering prescriptive solutions, my aim is to stimulate a broader conversation about the implications of GenAI in academic writing.

The current state of GenAI use in writing can be summarized as follows:

1. GenAI regulations in writing are not yet standardized(1,3). While many journals allow its use for "readability improvement", the term is open to interpretation. Some authors might use ChatGPT to generate entire manuscripts from key findings, while others employ it solely as a grammar checker. This creates room for non-declaration of GenAI use.

2. Tools designed to detect AI-generated manuscripts are imperfect and likely to remain so(4), especially when humans extensively edit AI-generated texts.

3. Given appropriate input, AI can generate manuscripts that are as readable as those written by humans(5). Many authors, especially less experienced ones, are likely to rely on AI(4,5), and this tendency is expected to continue.

4. The push for work-life balance constrains the time physicians can dedicate to sentence-by-sentence reflection, making AI use in academic writing inevitable, especially for non-native authors.

These factors create a complex unresolved issue that stakeholders will continue to grapple with(4). The challenge lies in striking a balance between genuine human writing and reliance on AI(1,4). Achieving a universally acceptable balance seems elusive, as opinions on the matter tend to be highly subjective. What will the future of paper writing look like? I will illustrate one possible, albeit extreme scenario that may, paradoxically, help clarify or even resolve this conundrum.

In the future, medical papers may resemble a "dictionary", losing the element of "how it's written". Traditionally, we have valued both content ("what is written") and tone ("how it is written") in medical papers. An extreme example of the latter is seen in "human touch" (anecdotes, experiential insights, and proverbial wisdom). This touch enriches manuscripts(5). However, we may need to abandon such touch or tone.

A dictionary? Nobody minds its "flat" descriptions. We do not expect a writing tone from it: accuracy and thus "what is written" matters. If "dictionary-like papers" is difficult to imagine, consider an anatomy textbook, where most pages feature straightforward factual statements.

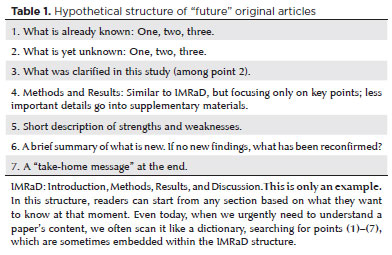

I anticipate that future papers will become more formulaic and dry, resembling a dictionary or an anatomy textbook. For instance, essential information may be condensed into bullet-point formats (Table 1), replacing the traditional IMRaD (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) style. Once adapted, this style may enable readers to rapidly grasp core points, much like referencing a dictionary.

A bullet-point style manuscript may require minimal writing finesse, freeing authors from concerns about tone and style. By excluding these elements, reliance on AI decreases, leaving only the content. Writing bullet points is straightforward, making AI assistance less necessary. Thus, AI reliance will naturally wane. I am not dismissing the value of IMRaD; with over 590 PubMed-indexed papers under my belt, I respect its merits, forged through the persistent efforts of many. Still, I foresee a shift. IMRaD may not be eternal.

This bullet-point style comes with a cost: the loss of individual tone and writing flair. I fervently hope Editorials, Opinions, and Letters remain the domain of human writers. In these "thought-expressing pieces", "how it is written" holds significant weight(5). If original papers lose this element, such pieces will become even more important.

Perhaps journals will resemble a "column among data books", with thought-expressing pieces serving as columns where the role of authors as "writers" is preserved.

I expect the academic community to find solutions that balance AI's benefits with preserving individuality in writing, rendering my concerns moot. I hope this is the case. Even in a worst-case scenario, I believe that individuality can still be expressed in subtle details. Just as high-school students in identical uniforms can express themselves through small touches, like a red lining, humans are wired to notice and appreciate these nuances.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

A part of the present concept was previously described and cited.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS:

Significant contribution to conception and design: Shigeki Matsubara. Data acquisition: Shigeki Matsubara. Data analysis and interpretation: Shigeki Matsubara. Manuscript drafting: Shigeki Matsubara. Significant intellectual content revision of the manuscript: Shigeki Matsubara. Final approval of the submitted manuscript: Shigeki Matsubara. Statistical analysis: Shigeki Matsubara. Obtaining funding: not applicable. Supervision of administrative, technical, or material support: Shigeki Matsubara. Research group leadership: Shigeki Matsubara.

REFERENCES

1. Liu Y, Kong W, Merve K. ChatGPT applications in academic writing: a review of potential, limitations, and ethical challenges. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2025;88(3):e2024-0269.

2. Ambrósio R Jr, Costa Neto AB, Magalhães MP, Yogi M, Pereira K, Machado AP. Ethical implications of using artificial intelligence to support scientific writing. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2025;88(2):e2025- 0018.

3. Else H. Group to establish standards for AI in papers. Science. 2024;384(6693):261.

4. França TFA, Monserrat JM. The artificial intelligence revolution... in unethical publishing: will AI worsen our dysfunctional publishing system? J Gen Physiol. 2024;156(11):e202413654.

5. Matsubara S, Matsubara D. What’s the difference between human-written manuscripts versus ChatGPT-generated manuscripts involving “human touch”? J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2025; 51(2):e16226.

Response to the Letter

We sincerely appreciate the interest and constructive comments from Shigeki Matsubara regarding our article. His vision of a potential "dictionary-like" future for medical papers raises important questions about the balance between efficiency and individuality in scholarly communication. We are grateful for the opportunity to respond to his concerns and share our perspective.

Shigeki Matsubara's apocalyptic prediction of "dictionary-like" medical writing fundamentally misattributes technological limitations to governance failures—a diagnostic error requiring urgent rectification. While his concerns about erosion of narrative merit consideration, the proposed bullet-point paradigm perilously oversimplifies the issue and its solutions. We reframe this debate through three dialectical lenses: (1) empirical evidence of narrative's irreplaceable clinical value; (2) AI's emerging ability to craft context-sensitive writing under appropriate constraints; and (3) next-generation accountability frameworks that transcend declaration checklists.

The cognitive science of clinical decision-making debunks Matsubara's false content-vs-narrative dichotomy. IMRaD-formatted abstracts enhance clarity and comprehension of clinical research by presenting causal reasoning in a logical sequence, thereby improving clinical decision-making(1). This advantage is particularly pronounced in immunotherapy, where the 2020 ESMO Quality Checklist mandates detailed descriptions of biomarker-treatment response dynamics(2)—a complexity that bullet points struggle to convey. Concurrently, specialized AI models like MedPaLM2 (trained on 4.7 million EHRs) match human performance in patient-centered discussions when guided by precision prompts(3). The issue lies not with AI's limitations, but with our failure to institutionalize strategic prompting protocols.

Current GenAI governance resembles a sieve through which accountability drains. While Matsubara rightly critiques declaration ambiguities, he misses systemic solutions. Recent frameworks suggest leveraging data provenance and blockchain technologies to trace and verify human contributions in AI-assisted research, increasing transparency and accountability(4). Pilot initiatives at several journals, including those in the Lancet family, have shown that enhanced AI transparency policies, paired with screening tools, can significantly improve disclosure compliance, although exact figures vary across institutions. For high-risk applications like hypothesis generation, we further mandate transparency in training data (excluding retracted studies) and demographic parity audits that align with Global Burden of Disease metrics.

Quantifying "human touch" transforms abstract concerns into actionable policies. Our Narrative Uniqueness Index (NUI)—a weighted composite of lexical diversity, conceptual novelty, and rhetorical signature—reveals that human-AI collaborations outperform pure AI texts in conceptual innovation, though they lag in lexical richness(5). The Gates Foundation has long invested in global health innovation, including AI-driven research, through initiatives like Grand Challenges and Open Research platforms, promoting ethical and transparent scientific practices(6). Integrating NUI metrics could incentivize narrative rigor, but would require interdisciplinary collaboration between computational linguists and journal editors.

Redefining authorship requires shifting from prose generation to strategic curation. ICMJE criteria should be updated to mandate prompt engineering logs (documenting iterations, such as "Prompt v4.3 added health equity constraints") and patient co-review of AI-drafted lay summaries (readability ≤8th-grade level). Major medical journals, like BMJ, are increasingly rejecting AI-assisted submissions due to inadequate validation and insufficient transparency about data sources and ethical compliance(7), epitomizing this paradigm shift.

The evolution of research methodology demands discipline-specific adaptations rather than universal templates. Current reporting standards for AI interventions, such as the CONSORT-AI 2020 guidelines(8), provide frameworks for clinical trials but need supplementary protocols for automated adverse event documentation. Qualitative research shows that while AI tools aid transcription and interpretation, they can produce misleading results and lack depth without human validation(9). Combining structured clinician reflexivity statements with AI-processed notes may improve patient-centered outcomes compared to AI-only documentation. However, these approaches need further validation across diverse clinical settings.

In conclusion, let us retire false dichotomies. The true peril lies not in AI's ascendance but in our failure to adapt governance infrastructures. By integrating blockchain provenance, NUI metrics, and precision formatting, we can create a symbiotic ecosystem where AI amplifies rather than extinguishes human insight. This future is neither a sterile dictionary nor a utopia, but a balanced evolution. We appreciate Dr. Matsubara's insightful comments, which have enriched the discussion on AI's role in academic writing. We are committed to advancing this dialogue and contributing to the development of ethical and effective practices in scientific communication.

REFERENCES

1. Guimarães CA. Structured abstracts: narrative review. Acta Cir Bras. 2006;21(4):263-8.

2. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Reporting standards for cancer immunotherapy: the ESMO quality checklist. Ann Oncol. 2020; 31(12):1657-61.

3. Zhang Y, LeCun Y, Bengio S. Domain-specific fine-tuning of large language models for hypothesis-driven writing. Nat Mach Intell. 2025;7(4):201-10.

4. Werder K, Ramesh B, Zhang R. Establishing data provenance for responsible artificial intelligence systems. ACM Trans Manag Inf Syst. 2022;13:1-23.

5. Hubert KF, Awa KN, Zabelina DL. The current state of artificial intelligence generative language models is more creative than humans on divergent thinking tasks. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):3440.

6. Farley A, Aspaas PP. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation as promoter of Open Research. Open Sci Talk. 2023;49. https://doi. org/10.7557/19.6945.

7. Ali MJ. The science and philosophy of manuscript rejection. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(7):1934-5.

8. Liu X, Cruz Rivera S, Moher D, Calvert MJ, Denniston AK; SPIRIT-AI and CONSORT-AI Working Group. Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the CONSORT-AI extension. Nat Med. 2020;26(9):1364-74.

9. Budhwar P, Chowdhury S, Wood G, Aguinis H, Bamber GJ, Beltran JR, et al. 2023. Human resource management in the age of generative artificial intelligence: Perspectives and research directions on ChatGPT. J Hum Resour Manag. 2023;33(3):606-59.

Dear Editor,

We sincerely appreciate Professor Matsubara's thoughtful response to our article on the ethical implications of using artificial intelligence in scientific writing(1). His comments resonate with our central concern: the risk of transforming scientific production into a hollow process-paradoxically efficient but saturated, overpolished, and often lacking in relevance or impact.

As modern stoics might put it: "Tools multiply our power; wisdom directs it. Without purpose, even the most efficient blade cuts blindly." This sentiment encapsulates the dual nature of our present challenge. The tools that enable unprecedented productivity can, if misused, foster a culture of superficiality unless guided by a clear purpose.

This balance underpins our proposed (A2I)2 algorithm, which combines Applied Ancient Intelligence and Applied Artificial Intelligence(2). The former provides a philosophical perspective—the "why"—rooted in efficacy, discernment, purpose, and responsibility. The latter provides the technical means—the "how"—to act with efficiency, precision, and scale. Without purpose, efficiency is mere noise, but when aligned, they enable us to act with wisdom and meaning.

An alarming trend reinforces this concern: the sharp increase in authors publishing over sixty articles annually, effectively, one paper every five days. Initially highlighted by Loannidis et al. and later revisited by Conroy(3), this phenomenon raises ethical questions about productivity, authenticity, authorship, and the very nature of academic contribution. When output outpaces reflection, scientific integrity is compromised.

Recent analyses have revealed an exponential increase in rare, AI-favored words, such as "meticulous," "intricate," and "commendable," in scientific literature starting from 2023(4). This linguistic fingerprint suggests a growing reliance on generative models, often undetected and undisclosed. The concern escalates when such content is reviewed by peers who also rely on AI tools. We risk creating a self-reinforcing loop of publications written and evaluated by algorithms, with diminishing human management, leading to decreased originality and purpose. Perhaps the issue is not AI itself, but rather a lack of knowledge on how to effectively utilize it in academic writing. As AI adapts to its user's voice and style, it can be a powerful tool if judiciously applied.

We also agree with Matsubara's observation: if everything starts to look and sound the same—in language, structure, and even visuals—the human element becomes not just vital but indispensable. Uniformity dulls attention; originality engages it. As we get accustomed to recognizing what is formulaic, authentic voices will stand out even more, cutting through the noise and resonating with readers.

Furthermore, while AI can greatly facilitate literature reviews, refine writing styles, and expedite the preliminary organization of research content, we must recognize its limitations. AI remains a powerful tool, but it can never replace the human intellect that conceives the fundamental questions and shapes the direction of inquiry.

At its core, scientific progress hinges on an investigator's curiosity, methodological rigor, and ethical considerations that cannot be automated. This synergy —where the researcher's insight fuels the "why," and AI provides a more efficient "how"—should be cultivated to enhance rather than supplant our ability to create meaningful work.

Ultimately, true creativity and impact stem from the human capacity to pose profound questions and contextualize findings within a larger framework, ensuring that scientific output retains its authenticity and transformative potential.

Paradoxically, AI may elevate the value of genuine human authorship. This letter, for instance, utilized GPT-4o to enhance clarity and flow, yet its originality, intention, and authorship remain entirely human and are anchored in group collaboration, reflection, responsibility, and our shared commitment to learning, evolving, and the future of science.

We appreciate Professor Matsubara's insightful contribution to this timely conversation, emphasizing the need for ethical clarity. Let us embrace innovation, without compromising the soul of scientific inquiry.

REFERENCES

1. Ambrósio R Jr, Costa Neto AB, Magalhães MP, Yogi M, Pereira K, Machado AP. Ethical implications of using artificial intelligence to support scientific writing. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2025;88(2):e20250018.

2. Ambrósio R Jr, Machado AP, Leão E, Lyra JM, Salomão MQ, Esporcatte LG, et al. Optimized artificial intelligence for enhanced ectasia detection using scheimpflug-based corneal tomography and biomechanical data. Am J Ophthalmol. 2023;251:126-42.

3. Conroy G. Surge in number of ‘extremely productive’ authors concerns scientists. Nature. 2024;625(7993):14-5.

4. ICML’24: Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning. Article No.: 1192, Pages 29575-620.

Submitted for publication:

March 10, 2025.

Accepted for publication:

March 14, 2025.

Editor-in-Chief: Newton Kara-Júnior Associate Editor: Newton Kara-Júnior

Funding: This study received no specific financial support.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest